Whole-class instruction includes read-alouds and shared reading, vocabulary, independent work, handwriting, and social development, and it is designed to be used in coordination with Small-Group Reading.

Research has shown us that the traditional whole-class phonics lesson is not the way to develop fluent readers— not for kindergarteners or, in fact, for students in any grade level. Whole-class phonics instruction assumes our students all have the same instructional needs, but we know this is not the case.

“Some teachers taught the curriculum today. Other teachers taught students today. And there’s a big difference.”

-Blunt Educator

IDENTITY

For students to be fully engaged in school, they must find it relevant. That starts with identity.

What it looks like in the classroom: Start by asking yourself, “How does my teaching and learning help students to learn about themselves and about others?”

SKILLS

So much of our current curricula and standards already focus on skills, so this part of the framework is nothing new; what’s important is to not throw it out when the other three layers are added.

You can have it all. You can have voice and fun and engagement and skills.

What it looks like in the classroom: Teaching skills is more or less what you’d expect typical school content to be, what our current standards are already prescribing. In ELA it can be citing textual evidence.

INTELLECT

Gholdy Muhammad urges us to ask What do we want our students to become smarter about?

Because our recent standards have been so skills-driven, knowledge has fallen by the wayside in a lot of schools, and that can strip away the joy that comes from simply learning new things about the world.

What it looks like in the classroom: When developing lessons and units, ask yourself, “How does my teaching and learning help to teach students new knowledge and concepts? New histories, new people, places, and things?”

CRITICALLY

“Criticality is helping students to read, write and think in active ways,” Muhammad explains, “as opposed to passive—when you ask a question and there’s one correct answer, and you just take it in. We don’t want them to be passive consumers of knowledge. We want them to question what they hear on the news.”

What it looks like in the classroom: “With criticality,” Muhammad says, “the teacher is asking, How does my teaching and learning help students to understand power, equity, anti-racism and anti-oppression? So (students are) reading, writing, thinking in active ways to understand power, inequality, equity, oppression. They’re investigating different standpoints, especially the marginalized point of view, and reading between the lines. In other words, reading for what’s not being said and for what’s not there.

1. Provide Direct, Explicit Instruction in Comprehension

2. Build Background Knowledge

3. Use Decodable Texts that Match Students’ Instructional Level

4. Encourage Rereading

5. Provide Time to Talk

6. Give Students to Opportunities to Write about Their Reading

Integrate opportunities for students to use their background knowledge, perspectives, and/or experiences to make a meaningful connection with the content.

Chunk your instruction (teacher-led) into meaningful and accessible ways. Ensure the lesson is aligned with the rigor of grade-level standards and expectations.

Provide your students with opportunities to actively process content that includes unstructured time to think. Promote academic discourse and connections with peers’ perspectives.

Give your students an opportunity to apply their new learning in a way that strengthens real-world connections and deepens their understanding.

Include elements that provide joy & reflection that utilize students’ interests and cultural perspectives that allow and encourage them to make connections to the content.

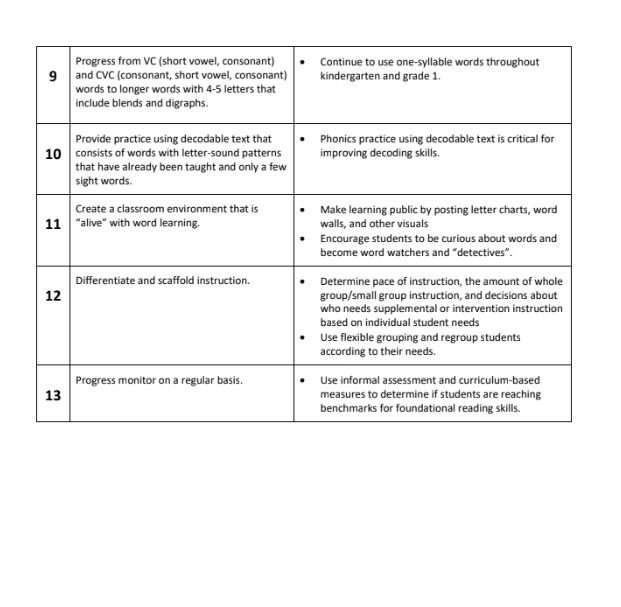

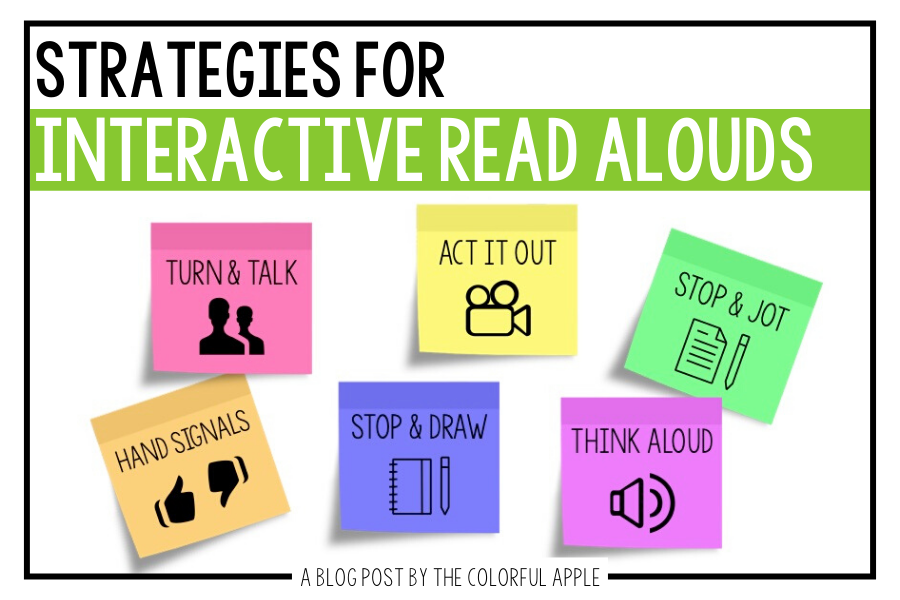

1. Interactive Read-Alouds with Think-Alouds

During read-alouds, the teacher models comprehension strategies (like predicting, questioning, and making inferences) while pausing to engage students in rich, text-based discussion.

Why it works: Think-alouds make invisible reading processes visible and accessible to students.

Evidence base: Research supports that teacher modeling during shared reading improves comprehension and vocabulary acquisition (McKeown & Beck, 2003).

2. Shared Reading with Repeated Texts

In shared reading, the whole class reads a text together with teacher support, often using big books or projected texts. Repeating texts across the week builds fluency and reinforces language patterns.

Why it works: Provides scaffolding for emergent and developing readers and promotes confidence.

Evidence base: Repeated exposure to the same text improves word recognition, phrasing, and oral fluency (Rasinski, 2012).

3. Turn-and-Talk with Structured Prompts

Students briefly turn to a partner to discuss a question, make a prediction, or explain a vocabulary word. Prompts should be purposeful and tied to the learning goal.

Why it works: Encourages every child to process ideas verbally, rather than relying on a few hands in the air.

Evidence base: Oral language opportunities increase comprehension and vocabulary development (August & Shanahan, 2006).

4. Anchor Charts and Visual Supports

Teachers and students co-create visual tools that capture key concepts, strategies, or steps in a process (e.g., “How to summarize” or “Parts of a paragraph”).

Why it works: Reinforces instruction over time and supports working memory, especially for English learners and students with processing needs.

Evidence base: Visual scaffolds increase accessibility and retention of content (Marzano, 2004).

5. Sentence Stems and Language Frames

During discussion or written response, provide sentence starters to support academic talk and written expression (e.g., “The author’s message is ___ because…”).

Why it works: Builds students’ confidence and equips them with the language of thinking and analysis.

Evidence base: Supports academic language development and improves comprehension in all learners, particularly multilingual students (Zwiers, 2014).

References

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McKeown, M. G., & Beck, I. L. (2003). Taking advantage of read-alouds to help children make sense of decontextualized language. In A. van Kleeck, S. A. Stahl, & E. B. Bauer (Eds.), On Reading Books to Children: Parents and Teachers (pp. 159–176). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Marzano, R. J. (2004). Building Background Knowledge for Academic Achievement: Research on What Works in Schools. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Rasinski, T. V. (2012). Why reading fluency should be hot. The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01077

Zwiers, J. (2014). Building Academic Language: Meeting Common Core Standards Across Disciplines, Grades 5–12 (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Make the Time Count!

-

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the understanding that spoken words are made up of smaller parts and these parts can be pulled apart into individual sounds.

-

Alphabet Knowledge

Once students have grasped that words are made up of individual sounds, it’s time to connect those sounds to printed symbols (letter or letter combinations). There are 44 sounds in the English language and MANY ways to represent these sounds. Begin with the letters of the alphabet, introducing their most common sounds first. Eventually, you will systematically introduce other letters and letter combinations (graphemes).

-

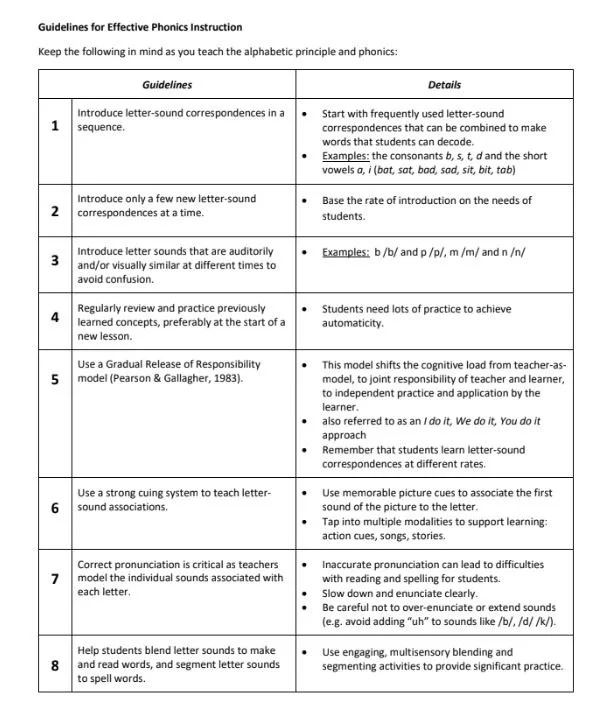

Phonics Instruction

Phonics is an essential component of reading instruction. It is especially important in the beginning stages of learning to read and is even more important with your students who are struggling with reading. The National Reading Panel determined that effective reading instruction includes a mixture of phonemic awareness, phonics, guided oral reading, and comprehension strategies.